Что каждый программист должен знать о памяти , часть 1

Сентябрь 21, 2007

Автор - Ulrich Drepper

1 Введение

Раньше компьютеры были проще.

Процессоры , память , устройства хранения были единым целым.

Например , память и сетевые устройства были сопоставимы по скорости работы с процессором.

Но с какого-то момента разработчики начали оптимизировать отдельные компоненты.

В результате некоторые из них резко упали в производительности.

Это касается устройств хранения и памяти.

Операционные системы хранят основные данные в памяти,которая в свою очередь быстрее

остальных устройств хранения . У последних появился кеш , который прозрачен для операционных систем.

В отличие от устройств хранения , оптимизация памяти - намного более сложный процесс ,

который подчас идет на уровне железа.

Это имеет следующие формы:

- RAM hardware design (speed and parallelism).

- Memory controller designs.

- CPU caches.

- Direct memory access (DMA) for devices.

В этом документе будет идти речь о кеше процессора и DMA,

будут рассмотрены различные типы RAM.

1.1 Структура документа

Документ предназначен для широкой массы разработчиков ,

и не все подробные детали описания железа будут расшифрованы.

Вторая часть описывает т.н. random-access memory (RAM),

и ее полное понимание необязательно для остальных частей.

Вы можете найти тут полезные ссылки.

Третья часть описывает CPU cache.

Она является ключевой для понимания оставшегося документа.

4-я часть описывает реализацию виртуальной памяти и также важна.

5-я часть описывает т.н. Non Uniform Memory Access (NUMA).

6-я часть - центральная в этом документе.

В ней подводятся предварительные итоги и даются советы программистам , как лучше писать

в различных ситуациях.

В принципе , чтение документа можно начать прямо с нее и потом возвращаться

по мере необходимости.

7-я часть посвящена всяким тулзам

8-я дает обзор перспективным технологиям будущего.

2 Commodity Hardware Today

Understanding commodity hardware is important because specialized

hardware is in retreat. Scaling these days is most often achieved

horizontally instead of vertically, meaning today it is more cost-effective

to use many smaller, connected commodity computers

instead of a few really large and exceptionally fast (and expensive)

systems. This is the case because fast and inexpensive network

hardware is widely available. There are still situations where the

large specialized systems have their place and these systems still

provide a business opportunity, but the overall market is dwarfed by

the commodity hardware market. Red Hat, as of 2007, expects that for

future products, the “standard building blocks” for most data

centers will be a computer with up to four sockets, each filled with a

quad core CPU that, in the case of Intel CPUs, will be

hyper-threaded. {Hyper-threading enables a single processor

core to be used for two or more concurrent executions with just a

little extra hardware.} This means the standard system in the data

center will have up to 64 virtual processors. Bigger machines will be

supported, but the quad socket, quad CPU core case is currently

thought to be the sweet spot and most optimizations are targeted for

such machines.

Large differences exist in the structure of commodity computers. That

said, we will cover more than 90% of such hardware by concentrating

on the most important differences. Note that these technical details

tend to change rapidly, so the the reader is advised to take the date

of this writing into account.

Over the years the personal computers and smaller servers standardized

on a chipset with two parts: the Northbridge and Southbridge.

Figure 2.1 shows this structure.

Figure 2.1: Structure with Northbridge and Southbridge

All CPUs (two in the previous example, but there can be more) are

connected via a common bus (the Front Side Bus, FSB) to the

Northbridge. The Northbridge contains, among other things, the memory

controller, and its implementation determines the type of RAM chips

used for the computer. Different types of RAM, such as DRAM, Rambus,

and SDRAM, require different memory controllers.

To reach all other system devices, the Northbridge must communicate with

the Southbridge. The Southbridge, often referred to as the I/O

bridge, handles communication with devices through a variety of

different buses. Today the PCI, PCI Express, SATA, and USB buses are

of most importance, but PATA, IEEE 1394, serial, and parallel ports

are also supported by the Southbridge. Older systems had AGP slots

which were attached to the Northbridge. This was done for performance

reasons related to insufficiently fast connections between the

Northbridge and Southbridge. However, today the PCI-E slots are all

connected to the Southbridge.

Such a system structure has a number of noteworthy consequences:

- All data communication from one CPU to another must travel over

the same bus used to communicate with the Northbridge.

- All communication with RAM must pass through the Northbridge.

- The RAM has only a single port.

{We will not discuss multi-port RAM in this document as this

type of RAM is not found in commodity hardware, at least not in places

where the programmer has access to it. It can be found in specialized

hardware such as network routers which depend on utmost speed.}

- Communication between a CPU and a device attached to the

Southbridge is routed through the Northbridge.

A couple of bottlenecks are immediately apparent in this design. One

such bottleneck involves access to RAM for devices. In the earliest

days of the PC, all communication with devices on either bridge had to

pass through the CPU, negatively impacting overall system performance.

To work around this problem some devices became capable of direct

memory access (DMA). DMA allows devices, with the help of the

Northbridge, to store and receive data in RAM directly without the

intervention of the CPU (and its inherent performance cost). Today all

high-performance devices attached to any of the buses can utilize DMA.

While this greatly reduces the workload on the CPU, it also creates

contention for the bandwidth of the Northbridge as DMA requests

compete with RAM access from the CPUs. This problem, therefore, must

to be taken into account.

A second bottleneck involves the bus from the Northbridge to the RAM.

The exact details of the bus depend on the memory types deployed.

On older systems there is only one bus to all the RAM chips, so

parallel access is not possible. Recent RAM types require

two separate buses (or channels as they are called for DDR2,

see Figure 2.8) which doubles the available bandwidth. The

Northbridge interleaves memory access across the channels. More

recent memory technologies (FB-DRAM, for instance) add more channels.

With limited bandwidth available, it is important to schedule memory

access in ways that minimize delays. As we will see, processors are much faster and

must wait to access memory, despite the use of CPU caches. If multiple

hyper-threads, cores, or processors access memory at the same time,

the wait times for memory access are even longer. This is also true

for DMA operations.

There is more to accessing memory than

concurrency, however. Access patterns themselves also greatly

influence the performance of the memory subsystem, especially with

multiple memory channels. Refer to Section 2.2 for more

details of RAM access patterns.

On some more expensive systems, the Northbridge does not actually

contain the memory controller. Instead the Northbridge can be

connected to a number of external memory controllers (in the following

example, four of them).

Figure 2.2: Northbridge with External Controllers

The advantage of this architecture is that more than one memory bus

exists and therefore total bandwidth increases. This design also

supports more memory. Concurrent memory access patterns reduce delays

by simultaneously accessing different memory banks. This is

especially true when multiple processors are directly connected to

the Northbridge, as in Figure 2.2. For such a design, the

primary limitation is the internal bandwidth of the Northbridge, which

is phenomenal for this architecture (from Intel). {For

completeness it should be mentioned that such a memory controller

arrangement can be used for other purposes such as “memory RAID”

which is useful in combination with hotplug memory.}

Using multiple external memory controllers is not the only way to

increase memory bandwidth. One other increasingly popular way is to integrate

memory controllers into the CPUs and attach memory to each CPU. This

architecture is made popular by SMP systems based on AMD's Opteron

processor. Figure 2.3 shows such a system. Intel will have

support for the Common System Interface (CSI) starting with the

Nehalem processors; this is basically the same approach: an integrated

memory controller with the possibility of local memory for each

processor.

Figure 2.3: Integrated Memory Controller

With an architecture like this there are as many memory banks

available as there are processors. On a quad-CPU machine the memory

bandwidth is quadrupled without the need for a complicated Northbridge with

enormous bandwidth. Having a memory controller integrated into the

CPU has some additional advantages; we will not dig deeper into this

technology here.

There are disadvantages to this architecture, too. First of all,

because the machine still has to make all the memory of the system

accessible to all processors, the memory is not uniform anymore (hence

the name NUMA - Non-Uniform Memory Architecture - for such an architecture).

Local memory (memory attached to a processor)

can be accessed with the usual speed. The situation is different when

memory attached to another processor is accessed. In this case

the interconnects between the processors have to be used. To access

memory attached to CPU2 from CPU1 requires communication across one

interconnect. When the same CPU accesses memory attached to

CPU4 two interconnects have to be crossed.

Each such communication has an associated cost. We talk about “NUMA

factors” when we describe the extra time needed to access remote

memory. The example architecture in Figure 2.3 has two

levels for each CPU: immediately adjacent CPUs and one CPU

which is two interconnects away. With more

complicated machines the number of levels can grow significantly. There are

also machine architectures (for instance IBM's x445 and SGI's

Altix series) where there is more than one type of connection. CPUs

are organized into nodes; within a node the time to access the

memory might be uniform or have only small NUMA factors. The

connection between nodes can be very expensive, though, and the NUMA

factor can be quite high.

Commodity NUMA machines exist today and will likely play an even greater

role in the future. It is expected that, from late 2008 on, every SMP

machine will use NUMA. The costs associated with NUMA make it important to

recognize when a program is running on a NUMA machine. In

Section 5 we will discuss more machine architectures and some

technologies the Linux kernel provides for these programs.

Beyond the technical details described in the remainder of this

section, there are several additional factors which influence the

performance of RAM. They are not controllable by software, which is

why they are not covered in this section. The interested reader can

learn about some of these factors in Section 2.1. They are really

only needed to get a more complete picture of RAM technology and

possibly to make better decisions when purchasing computers.

The following two sections discuss hardware details at the gate level

and the access protocol between the memory controller and the DRAM

chips. Programmers will likely find this information enlightening since these

details explain why RAM access works the way it does. It is optional

knowledge, though, and the reader anxious to get to topics with more

immediate relevance for everyday life can jump ahead to

Section 2.2.5.

2.1 RAM Types

There have been many types of RAM over the years and each type

varies, sometimes significantly, from the other. The older types are

today really only interesting to the historians. We will not explore

the details of those. Instead we will concentrate on modern RAM types;

we will only scrape the surface, exploring some details which are

visible to the kernel or application developer through their

performance characteristics.

The first interesting details are centered around the question why

there are different types of RAM in the same machine. More

specifically, why there are both static RAM (SRAM {In other contexts

SRAM might mean “synchronous RAM”.}) and dynamic RAM (DRAM). The

former is much faster and provides the same functionality. Why is not

all RAM in a machine SRAM? The answer is, as one might expect, cost.

SRAM is much more expensive to produce and to use than DRAM. Both

these cost factors are important, the second one increasing in

importance more and more. To understand these difference we look at

the implementation of a bit of storage for both SRAM and DRAM.

In the remainder of this section we will discuss some low-level

details of the implementation of RAM. We will keep the level of detail as

low as possible. To that end, we will discuss the signals at a “logic level” and not at

a level a hardware designer would have to use. That level of detail

is unnecessary for our purpose here.

2.1.1 Static RAM

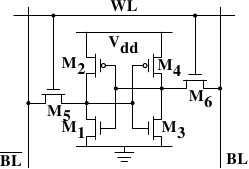

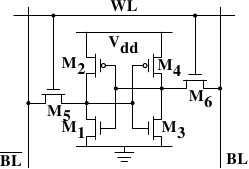

Figure 2.4: 6-T Static RAM

Figure 2.4 shows the structure of a 6 transistor SRAM cell.

The core of this cell is formed by the four transistors M1

to M4 which form two cross-coupled inverters. They have

two stable states, representing 0 and 1 respectively. The state is

stable as long as power on Vdd is available.

If access to the state of the cell is needed the word access line

WL is raised. This makes the state of the cell immediately

available for reading on BL and

BL. If the cell state must be

overwritten the BL and BL

lines are first set to the desired values and then WL is

raised. Since the outside drivers are stronger than the four

transistors (M1 through M4) this

allows the old state to be overwritten.

See [sramwiki] for a more detailed on the way the cell works.

For the following discussion it is important to note that

- one cell requires six transistors. There are variants with four

transistors but they have disadvantages.

- maintaining the state of the cell requires constant power.

- the cell state is available for reading almost immediately once

the word access line WL is raised. The signal is as rectangular

(changing quickly between the two binary states) as

other transistor-controlled signals.

- the cell state is stable, no refresh cycles are needed.

There are other slow and less power-hungry SRAM forms available, but

those are not of interest here since we are looking at fast RAM.

These slow variants are mainly interesting because they can be more

easily be used in a system than a dynamic RAM chip because of their

simpler interface.

2.1.2 Dynamic RAM

Dynamic RAM is, in its structure, much simpler than static RAM.

Figure 2.5 shows the structure of a usual DRAM cell design.

All it consists of is one transistor and one capacitor. This huge

difference in complexity of course means that it functions very differently

than static RAM.

Figure 2.5: 1-T Dynamic RAM

A dynamic RAM cell keeps its state in the capacitor C. The

transistor M is used to guard the access to the state. To

read the state of the cell the access line AL is raised;

this either causes a current to flow on the data line DL or

not, depending on the charge in the capacitor. To write to the cell the

data line DL is appropriately

set and then AL is raised for a time long enough to charge or

drain the capacitor.

There are a number of complications with the design of dynamic RAM.

The use of a capacitor means that reading the cell discharges the

capacitor. The procedure cannot be repeated indefinitely, the

capacitor must be recharged at some point. Even worse, to accommodate

the huge number of cells (chips with 109 or more cells are now

common) the capacity to the capacitor must be low (in the femto-farad range

or lower). A fully charged capacitor holds a few 10's of thousands of

electrons. Even though the resistance of the capacitor is high (a

couple of tera-ohms) it only takes a short time for the capacity to

dissipate. This problem is called “leakage”.

This leakage is why a DRAM cell must be constantly refreshed. For most DRAM

chips these days this refresh must happen every 64ms. During the refresh cycle no access to

the memory is possible. For some workloads this overhead might stall

up to 50% of the memory accesses (see [highperfdram]).

A second problem resulting from the tiny charge is that the

information read from the cell is not directly usable. The data line

must be connected to a sense amplifier which can distinguish between

a stored 0 or 1 over the whole range of charges which still have to

count as 1.

A third problem is that charging and draining a capacitor is not

instantaneous. The signals received by the sense amplifier are not

rectangular, so a conservative estimate as to when the output of the

cell is usable has to be used. The formulas for charging and

discharging a capacitor are

![[Formulas]](images/capcharge.png)

This means it takes some time (determined by the capacity C and

resistance R) for the capacitor to be charged and discharged. It also

means that the current which can be detected by the sense amplifiers

is not immediately available. Figure 2.6 shows the charge and

discharge curves. The X—axis is measured in units of RC (resistance

multiplied by capacitance) which is a unit of time.

Figure 2.6: Capacitor Charge and Discharge Timing

Unlike the static RAM case where the output is immediately available when

the word access line is raised, it will always take a bit of time until the

capacitor discharges sufficiently. This delay severely limits how fast

DRAM can be.

The simple approach has its advantages, too. The main advantage is

size. The chip real estate needed for one DRAM cell is many times

smaller than that of an SRAM cell. The SRAM cells also need

individual power for the transistors maintaining the state. The

structure of the DRAM cell is also simpler and more regular which

means packing many of them close together on a die is simpler.

Overall, the (quite dramatic) difference in cost wins. Except in

specialized hardware — network routers, for example — we have to live with main memory

which is based on DRAM. This has huge implications on the programmer

which we will discuss in the remainder of this paper. But first we need

to look into a few more details of the actual use of DRAM cells.

2.1.3 DRAM Access

A program selects a memory location using a virtual address. The

processor translates this into a physical address and finally the

memory controller selects the RAM chip corresponding to that address. To

select the individual memory cell on the RAM chip, parts of the

physical address are passed on in the form of a number of address

lines.

It would be completely impractical to address memory locations

individually from the memory controller: 4GB of RAM would require

232 address lines.

Instead the address is passed encoded as a binary number using a

smaller set of address lines. The address passed to the DRAM chip

this way must be demultiplexed first. A demultiplexer with N

address lines will have 2N output lines. These output lines can be

used to select the memory cell. Using this direct approach is no big

problem for chips with small capacities.

But if the number of cells grows this approach is not suitable

anymore. A chip with 1Gbit

{I hate those SI prefixes. For me

a giga-bit will always be 230 and not 109 bits.}

capacity

would need 30 address lines and 230 select lines. The size of a

demultiplexer increases exponentially with the number of input lines

when speed is not to be sacrificed. A demultiplexer for 30 address

lines needs a whole lot of chip real estate in addition to the

complexity (size and time) of the demultiplexer. Even more

importantly, transmitting 30 impulses on the address lines

synchronously is much harder than transmitting “only” 15 impulses.

Fewer lines have to be laid out at exactly the same length or timed

appropriately. {Modern DRAM types like DDR3 can automatically

adjust the timing but there is a limit as to what can be tolerated.}

Figure 2.7: Dynamic RAM Schematic

Figure 2.7 shows a DRAM chip at a very high level. The DRAM

cells are organized in rows and columns. They could all be aligned in

one row but then the DRAM chip would need a huge demultiplexer. With

the array approach the design can get by with one demultiplexer and

one multiplexer of half the size. {Multiplexers and

demultiplexers are equivalent and the multiplexer here needs to work

as a demultiplexer when writing. So we will drop the differentiation

from now on.} This is a huge saving on all fronts. In the example

the address lines

a0 and

a1 through the row address

selection

(RAS)

demultiplexer select the address lines of a whole row of cells. When

reading, the content of all cells is thusly made available to the

column address selection

(CAS)

{The line over the name

indicates that the signal is negated} multiplexer. Based on the

address lines a2 and

a3 the content of one column is

then made available to the data pin of the DRAM chip. This happens

many times in parallel on a number of DRAM chips to produce a total

number of bits corresponding to the width of the data bus.

For writing, the new cell value is put on the data bus and, when the

cell is selected using the RAS and CAS, it is stored in the cell.

A pretty straightforward design. There are in reality — obviously — many

more complications. There need to be specifications how much delay there

is after the signal before the data will be available on the data bus for

reading. The capacitors do not unload instantaneously, as described

in the previous section. The signal from the cells is so weak that

it needs to be amplified. For writing it must be specified how long

the data must be available on the bus after the RAS and CAS is

done to successfully store the new value in the cell (again, capacitor

do not fill or drain instantaneously). These timing constants are

crucial for the performance of the DRAM chip. We will talk about this

in the next section.

A secondary scalability problem is that having 30 address lines

connected to every RAM chip is not feasible either. Pins of a chip

are a precious resources. It is “bad” enough that the data must be

transferred as much as possible in parallel (e.g., in 64 bit batches).

The memory controller must be able to address each RAM module

(collection of RAM chips). If parallel access to multiple RAM modules

is required for performance reasons and each RAM module requires its own

set of 30 or more address lines, then the memory controller needs to

have, for 8 RAM modules, a whopping 240+ pins only for the address

handling.

To counter these secondary scalability problems DRAM chips have, for a long

time, multiplexed the address itself. That means the address is

transferred in two parts. The first part consisting of address bits

a0 and

a1 in the example in

Figure 2.7) select the row. This selection remains active

until revoked. Then the second part, address bits

a2 and

a3, select the column. The

crucial difference is that only two external address lines are needed.

A few more lines are needed to indicate when the RAS and CAS signals

are available but this is a small price to pay for cutting the number

of address lines in half. This address multiplexing brings its own

set of problems, though. We will discuss them in Section 2.2.

2.1.4 Conclusions

Do not worry if the details in this section are a bit overwhelming.

The important things to take away from this section are:

- there are reasons why not all memory is SRAM

- memory cells need to be individually selected to be used

- the number of address lines is directly responsible for the cost

of the memory controller, motherboards, DRAM module, and DRAM chip

- it takes a while before the results of the read or write

operation are available

The following section will go into more details about the actual

process of accessing DRAM memory. We are not going into more details

of accessing SRAM, which is usually directly addressed. This happens

for speed and because the SRAM memory is limited in size. SRAM is

currently used in CPU caches and on-die where the connections are small

and fully under control of the CPU designer. CPU caches are a topic

which we discuss later but all we need to know is that SRAM cells have

a certain maximum speed which depends on the effort spent on the

SRAM. The speed can vary from only slightly slower than the CPU core

to one or two orders of magnitude slower.

2.2 DRAM Access Technical Details

In the section introducing DRAM we saw that DRAM chips multiplex the

addresses in order to save resources. We also saw that accessing DRAM

cells takes time since the capacitors in those cells do not discharge instantaneously

to produce a stable signal; we also saw that DRAM cells must be

refreshed. Now it is time to put this all together and see how all

these factors determine how the DRAM access has to happen.

We will concentrate on current technology; we will not discuss

asynchronous DRAM and its variants as they are simply not relevant

anymore. Readers interested in this topic are referred to

[highperfdram] and [arstechtwo]. We will also not talk about

Rambus DRAM (RDRAM) even though

the technology is not obsolete. It is just not widely used for system

memory. We will concentrate exclusively

on Synchronous DRAM (SDRAM) and its successors Double Data Rate DRAM

(DDR).

Synchronous DRAM, as the name suggests, works relative to a time

source. The memory controller provides a clock, the frequency of

which determines the speed of the Front Side Bus (FSB) —

the memory controller interface used by the DRAM chips. As of this writing,

frequencies of 800MHz, 1,066MHz, or even 1,333MHz are available with

higher frequencies (1,600MHz) being announced for the next generation. This

does not mean the frequency used on the bus is actually this high.

Instead, today's buses are double- or quad-pumped, meaning that data is

transported two or four times per cycle. Higher numbers sell so the

manufacturers like to advertise a quad-pumped 200MHz bus as an

“effective” 800MHz bus.

For SDRAM today each data transfer consists of 64 bits — 8 bytes. The

transfer rate of the FSB is therefore 8 bytes multiplied by the effective

bus frequency (6.4GB/s for the quad-pumped 200MHz bus). That sounds a

lot but it is the burst speed, the maximum speed which will never be

surpassed. As we will see now the protocol for talking

to the RAM modules has a lot of downtime when no data can be transmitted.

It is exactly this downtime which we must understand and minimize to

achieve the best performance.

2.2.1 Read Access Protocol

Figure 2.8: SDRAM Read Access Timing

Figure 2.8 shows the activity on some of the connectors of

a DRAM module which happens in three differently colored phases. As

usual, time flows from left to right. A lot of details are left out.

Here we only talk about the bus clock, RAS and CAS signals, and

the address and data buses. A read cycle begins with the memory

controller making the row address available on the address bus and

lowering the RAS signal. All signals are read on the rising edge

of the clock (CLK) so it does not matter if the signal is not

completely square as long as it is stable at the time it is read.

Setting the row address causes the RAM chip to start latching the

addressed row.

The CAS signal can be sent after tRCD (RAS-to-CAS Delay)

clock cycles. The column address is then transmitted by making it

available on the address bus and lowering the CAS line. Here we

can see how the two parts of the address (more or less halves, nothing

else makes sense) can be transmitted over the same address bus.

Now the addressing is complete and the data can be transmitted. The

RAM chip needs some time to prepare for this. The delay is usually

called CAS Latency (CL). In Figure 2.8 the CAS

latency is 2. It can be higher or lower, depending on the quality of

the memory controller, motherboard, and DRAM module. The latency can

also have half values. With CL=2.5 the first data would be available

at the first falling flank in the blue area.

With all this preparation to get to the data it would be wasteful to

only transfer one data word. This is why DRAM modules allow the

memory controller to specify how much data is to be transmitted.

Often the choice is between 2, 4, or 8 words. This allows filling

entire lines in the caches without a new RAS/CAS sequence. It is also

possible for the memory controller to send a new CAS signal without

resetting the row selection. In this way, consecutive memory addresses

can be read from or written to significantly faster because

the RAS signal does not have to be sent and the row does

not have to be deactivated (see below). Keeping the row “open” is

something the memory controller has to decide. Speculatively leaving

it open all the time has disadvantages with real-world applications

(see [highperfdram]). Sending new CAS signals is only subject

to the Command Rate of the RAM module (usually specified as Tx,

where x is a value like 1 or 2; it will be 1 for high-performance DRAM

modules which accept new commands every cycle).

In this example the SDRAM spits out one word per cycle. This is what

the first generation does. DDR is able to transmit two words per

cycle. This cuts down on the transfer time but does not change the

latency. In principle, DDR2 works the same although in practice it

looks different. There is no need to go into the details here. It is

sufficient to note that DDR2 can be made faster, cheaper, more

reliable, and is more energy efficient (see [ddrtwo] for more

information).

2.2.2 Precharge and Activation

Figure 2.8 does not cover the whole cycle. It only shows

parts of the full cycle of accessing DRAM. Before a new RAS signal

can be sent the currently latched row must be deactivated and the new

row must be precharged. We can concentrate here on the case where

this is done with an explicit command. There are improvements to the

protocol which, in some situations, allows this extra step to be avoided. The

delays introduced by precharging still affect the operation, though.

Figure 2.9: SDRAM Precharge and Activation

Figure 2.9 shows the activity starting from one CAS

signal to the CAS signal for another row. The data requested with

the first CAS signal is available as before, after CL cycles. In the

example two words are requested which, on a simple SDRAM, takes two

cycles to transmit. Alternatively, imagine four words on a DDR chip.

Even on DRAM modules with a command rate of one the precharge command

cannot be issued right away. It is necessary to wait as long as it

takes to transmit the data. In this case it takes two cycles. This

happens to be the same as CL but that is just a coincidence. The

precharge signal has no dedicated line; instead, some implementations

issue it by

lowering the Write Enable (WE) and RAS line simultaneously. This

combination has no useful meaning by itself (see [micronddr] for

encoding details).

Once the precharge command is issued it takes tRP (Row Precharge

time) cycles until the row can be selected. In Figure 2.9

much of the time (indicated by the purplish color) overlaps with the

memory transfer (light blue). This is good! But tRP is larger than

the transfer time and so the next RAS signal is stalled for one

cycle.

If we were to continue the timeline in the diagram we would find that

the next data transfer happens 5 cycles after the previous one stops.

This means the data bus is only in use two cycles out of seven.

Multiply this with the FSB speed and the theoretical 6.4GB/s for a

800MHz bus become 1.8GB/s. That is bad and must be avoided. The

techniques described in Section 6 help to raise this number.

But the programmer usually has to do her share.

There is one more timing value for a SDRAM module which we have not

discussed. In Figure 2.9 the precharge command was only

limited by the data transfer time. Another constraint is that an

SDRAM module needs time after a RAS signal before it can precharge

another row (denoted as tRAS). This number is usually pretty high,

in the order of two or three times the tRP value. This is a

problem if, after a RAS signal, only one CAS signal follows

and the data transfer is finished in a few cycles. Assume that in

Figure 2.9 the initial CAS signal was preceded directly

by a RAS signal and that tRAS is 8 cycles. Then the precharge

command would have to be delayed by one additional cycle since the sum of

tRCD, CL, and tRP (since it is larger than the data transfer time)

is only 7 cycles.

DDR modules are often described using a special notation: w-x-y-z-T.

For instance: 2-3-2-8-T1. This means:

| w | 2 | CAS Latency (CL) |

| x | 3 | RAS-to-CAS delay (tRCD) |

| y | 2 | RAS

Precharge (tRP) |

| z | 8 | Active to Precharge delay (tRAS) |

| T | T1 | Command Rate |

There are numerous other timing constants which affect the way

commands can be issued and are handled. Those five constants are in

practice sufficient to determine the performance of the module, though.

It is sometimes useful to know this information for the computers in

use to be able to interpret certain measurements. It is

definitely useful to know these details when buying computers since

they, along with the FSB and SDRAM module speed, are

among the most important factors determining a computer's speed.

The very adventurous reader could also try to tweak a system.

Sometimes the BIOS allows changing some or all these values. SDRAM

modules have programmable registers where these values can be set.

Usually the BIOS picks the best default value. If the quality of the

RAM module is high it might be possible to reduce the one or the other

latency without affecting the stability of the computer. Numerous

overclocking websites all around the Internet provide ample of

documentation for doing this. Do it at your own risk, though and do not say

you have not been warned.

2.2.3 Recharging

A mostly-overlooked topic when it comes to DRAM access is recharging.

As explained in Section 2.1.2, DRAM cells must constantly be refreshed.

This does not happen completely transparently for the rest of the

system. At times when a row {Rows are the granularity this

happens with despite what [highperfdram] and other literature

says (see [micronddr]).} is recharged no access is possible. The

study in [highperfdram] found that “[s]urprisingly, DRAM

refresh organization can affect performance dramatically”.

Each DRAM cell must be refreshed every 64ms according to the JEDEC

specification. If a DRAM array has 8,192 rows this means the memory

controller has to issue a refresh command on average every

7.8125µs (refresh commands can be queued so in practice the

maximum interval between two requests can be higher). It is the

memory controller's responsibility to schedule the refresh commands.

The DRAM module keeps track of the address of the last refreshed row

and automatically increases the address counter for each new request.

There is really not much the programmer can do about the refresh and

the points in time when the commands are issued. But it is important

to keep this part to the DRAM life cycle in mind when interpreting

measurements. If a critical word has to be retrieved from a row which

currently is being refreshed the processor could be stalled for quite a long

time. How long each refresh takes depends on the DRAM module.

2.2.4 Memory Types

It is worth spending some time on the current and soon-to-be current

memory types in use. We will start with SDR (Single Data Rate) SDRAMs

since they are the basis of the DDR (Double Data Rate) SDRAMs. SDRs

were pretty simple. The memory cells and the data transfer rate were

identical.

Figure 2.10: SDR SDRAM Operation

In Figure 2.10 the DRAM cell array can output the memory content at

the same rate it can be transported over the memory bus. If the DRAM

cell array can operate at 100MHz, the data transfer rate of the bus is thus

100Mb/s. The frequency f for all components is the same.

Increasing the throughput of the DRAM chip is expensive since the

energy consumption rises with the frequency. With a huge number of

array cells this is prohibitively expensive. {Power = Dynamic

Capacity Ч Voltage2 Ч Frequency.} In reality it is

even more of a problem since increasing the frequency usually also

requires increasing the voltage to maintain stability of the system.

DDR SDRAM (called DDR1

retroactively) manages to improve the throughput without increasing

any of the involved frequencies.

Figure 2.11: DDR1 SDRAM Operation

The difference between SDR and DDR1 is, as can be seen in

Figure 2.11 and guessed from the name, that twice the amount of

data is transported per cycle. I.e., the DDR1 chip transports data on

the rising and falling edge. This is sometimes called a

“double-pumped” bus. To make this possible without increasing the

frequency of the cell array a buffer has to be introduced. This

buffer holds two bits per data line. This in turn requires that, in

the cell array in Figure 2.7, the data bus consists of two

lines. Implementing this is trivial: one only has the use the same

column address for two DRAM cells and access them in parallel. The

changes to the cell array to implement this are also minimal.

The SDR

DRAMs were known simply by their frequency (e.g., PC100 for 100MHz

SDR). To make DDR1 DRAM sound better the marketers had to come up

with a new scheme since the frequency did not change. They came with

a name which contains the transfer rate in bytes a DDR module (they

have 64-bit busses) can sustain:

100MHz Ч 64bit Ч 2 = 1,600MB/s

Hence a DDR module with 100MHz frequency is called PC1600. With 1600

> 100 all marketing requirements are fulfilled; it sounds much

better although the improvement is really only a factor of

two. {I will take the factor of two but I do not have to like

the inflated numbers.}

Figure 2.12: DDR2 SDRAM Operation

To get even more out of the memory technology DDR2 includes a bit more

innovation. The most obvious change that can be seen in

Figure 2.12 is the doubling of the frequency of the bus.

Doubling the frequency means doubling the bandwidth. Since this

doubling of the frequency is not economical for the cell array it is

now required that the I/O buffer gets four bits in each clock cycle

which it then can send on the bus. This means the changes to the DDR2

modules consist of making only the I/O buffer component of the DIMM

capable of running at higher speeds. This is certainly possible and

will not require measurably more energy, it is just one tiny component and

not the whole module. The names the marketers came up with for DDR2

are similar to the DDR1 names only in the computation of the value the

factor of two is replaced by four (we now have a quad-pumped bus).

Figure 2.13 shows the names of the modules in use today.

Array

Freq. |

Bus

Freq. |

Data

Rate |

Name

(Rate) |

Name

(FSB) |

| 133MHz | 266MHz | 4,256MB/s | PC2-4200 | DDR2-533 |

| 166MHz | 333MHz | 5,312MB/s | PC2-5300 | DDR2-667 |

| 200MHz | 400MHz | 6,400MB/s | PC2-6400 | DDR2-800 |

| 250MHz | 500MHz | 8,000MB/s | PC2-8000 | DDR2-1000 |

| 266MHz | 533MHz | 8,512MB/s | PC2-8500 | DDR2-1066 |

Figure 2.13: DDR2 Module Names

There is one more twist to the naming. The FSB speed used by CPU,

motherboard, and DRAM module is specified by using the

effective frequency. I.e., it factors in the transmission

on both flanks of the clock cycle and thereby inflates

the number. So, a 133MHz module with a 266MHz bus has an FSB

“frequency” of 533MHz.

The specification for DDR3 (the real one, not the fake GDDR3 used in

graphics cards) calls for more changes along the lines of the

transition to DDR2. The voltage will be reduced from 1.8V

for DDR2 to 1.5V for DDR3. Since the power consumption equation is

calculated using the square of the voltage this alone brings a

30% improvement. Add to this a reduction in die size plus other

electrical advances and DDR3 can manage, at the same frequency, to get

by with half the power consumption. Alternatively, with higher

frequencies, the same power envelope can be hit. Or with double the

capacity the same heat emission can be achieved.

The cell array of DDR3 modules will run at a quarter of the speed of

the external bus which requires an 8 bit I/O buffer, up from 4 bits

for DDR2. See Figure 2.14 for the schematics.

Figure 2.14: DDR3 SDRAM Operation

Initially DDR3 modules will likely have slightly higher CAS

latencies just because the DDR2 technology is more mature. This would

cause DDR3 to be useful only at frequencies which are higher than those

which can be achieved with DDR2, and, even then, mostly when bandwidth is more

important than latency. There is already talk about 1.3V modules

which can achieve the same CAS latency as DDR2. In any case, the

possibility of achieving higher speeds because of faster buses will

outweigh the increased latency.

One possible problem with DDR3 is that, for 1,600Mb/s transfer rate or

higher, the number of modules per channel may be reduced to just one.

In earlier versions this requirement held for all frequencies, so

one can hope that the requirement will at some point be lifted for all

frequencies. Otherwise the capacity of systems will be severely limited.

Figure 2.15 shows the names of the expected DDR3 modules.

JEDEC agreed so far on the first four types. Given that Intel's 45nm

processors have an FSB speed of 1,600Mb/s, the 1,866Mb/s is needed for

the overclocking market. We will likely see more of this towards the end

of the DDR3 lifecycle.

Array

Freq. |

Bus

Freq. |

Data

Rate |

Name

(Rate) |

Name

(FSB) |

| 100MHz | 400MHz | 6,400MB/s | PC3-6400 | DDR3-800 |

| 133MHz | 533MHz | 8,512MB/s | PC3-8500 | DDR3-1066 |

| 166MHz | 667MHz | 10,667MB/s | PC3-10667 | DDR3-1333 |

| 200MHz | 800MHz | 12,800MB/s | PC3-12800 | DDR3-1600 |

| 233MHz | 933MHz | 14,933MB/s | PC3-14900 | DDR3-1866 |

Figure 2.15: DDR3 Module Names

All DDR memory has one problem: the increased bus frequency makes it

hard to create parallel data busses. A DDR2 module has 240 pins. All

connections to data and address pins must be routed so that they have

approximately the same length. Even more of a problem is that, if more

than one DDR module is to be daisy-chained on the same bus, the signals

get more and more distorted for each additional module. The DDR2

specification allow only two modules per bus (aka channel), the DDR3

specification only one module for high frequencies. With 240 pins per

channel a single Northbridge cannot reasonably drive more than two

channels. The alternative is to have external memory controllers (as

in Figure 2.2) but this is expensive.

What this means is that commodity motherboards are restricted to hold

at most four DDR2 or DDR3 modules. This restriction severely limits the

amount of memory a system can have. Even old 32-bit IA-32 processors

can handle 64GB of RAM and memory demand even for home use is growing,

so something has to be done.

One answer is to add memory controllers into each processor as

explained in Section 2. AMD does it with the Opteron

line and Intel will do it with their CSI technology. This will help

as long as the reasonable amount of memory a processor is able to use

can be connected to a single processor. In some situations this is

not the case and this setup will introduce a NUMA architecture and its negative

effects. For some situations another solution is needed.

Intel's answer to this problem for big server machines, at least for

the next years, is called Fully

Buffered DRAM (FB-DRAM). The FB-DRAM modules use the same components

as today's DDR2 modules which makes them relatively cheap to produce.

The difference is in the connection with the memory controller.

Instead of a parallel data bus FB-DRAM utilizes a serial bus (Rambus

DRAM had this back when, too, and SATA is the successor of PATA, as is

PCI Express for PCI/AGP). The serial bus can be driven at a much

higher frequency, reverting negative impact of the serialization and

even increase the bandwidth. The main effects of using a serial bus

are

- more modules per channel can be used.

- more channels per Northbridge/memory controller can be used.

- the serial bus is designed to be fully-duplex (two lines).

An FB-DRAM module has only 69 pins, compared with the 240 for DDR2.

Daisy chaining FB-DRAM modules is much easier since the electrical

effects of the bus can be handled much better. The FB-DRAM

specification allows up to 8 DRAM modules per channel.

Compared with the connectivity requirements of a dual-channel

Northbridge it is now possible to drive 6 channels of FB-DRAM with

fewer pins: 2Ч240 pins versus 6Ч69 pins. The routing

for each channel is much simpler which could also help reducing the

cost of the motherboards.

Fully duplex parallel busses are prohibitively expensive for the

traditional DRAM modules, duplicating all those lines is too costly.

With serial lines (even if they are differential, as FB-DRAM requires)

this is not the case and so the serial bus is designed to be fully

duplexed, which means, in some situations, that the bandwidth is theoretically

doubled alone by this. But it is not the only place where parallelism

is used for bandwidth increase. Since an FB-DRAM controller can run

up to six channels at the same time the bandwidth can be increased

even for systems with smaller amounts of RAM by using FB-DRAM. Where

a DDR2 system with four modules has two channels, the same capacity can

handled via four channels using an ordinary FB-DRAM controller. The

actual bandwidth of the serial bus depends on the type of DDR2 (or

DDR3) chips used on the FB-DRAM module.

We can summarize the advantages like this:

| DDR2 | FB-DRAM |

|

| Pins | 240 | 69 |

| Channels | 2 | 6 |

| DIMMs/Channel | 2 | 8 |

| Max Memory | 16GB | 192GB |

| Throughput | ~10GB/s | ~40GB/s |

There are a few drawbacks to FB-DRAMs if multiple DIMMs on one channel

are used. The signal is delayed—albeit minimally—at each DIMM in the

chain, which means the latency increases. But for the same amount of

memory with the same frequency FB-DRAM can always be faster than DDR2

and DDR3 since only one DIMM per channel is needed; for large

memory systems DDR simply has no answer using commodity components.

2.2.5 Conclusions

This section should have shown that accessing DRAM is not an

arbitrarily fast process. At least not fast compared with the speed

the processor is running and with which it can access registers and

cache. It is important to keep in mind the differences between CPU and

memory frequencies. An Intel Core 2 processor running at 2.933GHz and a

1.066GHz FSB have a clock ratio of 11:1 (note: the 1.066GHz bus is

quad-pumped). Each stall of one cycle on the memory bus means a stall

of 11 cycles for the processor. For most machines the actual DRAMs

used are slower, thusly increasing the delay. Keep these numbers in

mind when we are talking about stalls in the upcoming sections.

The timing charts for the read command have shown that DRAM modules

are capable of high sustained data rates. Entire DRAM rows could be

transported without a single stall. The data bus could be kept

occupied 100%. For DDR modules this means two 64-bit words

transferred each cycle. With DDR2-800 modules and two channels this

means a rate of 12.8GB/s.

But, unless designed this way, DRAM access is not always sequential.

Non-continuous memory regions are used which means precharging and new

RAS signals are needed. This is when things slow down and when the

DRAM modules need help. The sooner the precharging can happen and the

RAS signal sent the smaller the penalty when the row is actually

used.

Hardware and software prefetching (see Section 6.3) can be used

to create more overlap in the timing and reduce the stall.

Prefetching also helps shift memory operations in time so that there

is less contention at later times, right before the data is actually

needed. This is a frequent problem when the data produced in one

round has to be stored and the data required for the next round has to be

read. By shifting the read in time, the write and read operations do

not have to be issued at basically the same time.

2.3 Other Main Memory Users

Beside the CPUs there are other system components which can access the

main memory. High-performance cards such as network and mass-storage

controllers cannot afford to pipe all the data they need or provide

through the CPU. Instead, they read or write the data directly from/to

the main memory (Direct Memory Access, DMA). In Figure 2.1

we can see that the cards can talk through the South- and Northbridge

directly with the memory. Other buses, like USB, also require FSB

bandwidth—even though they do not use DMA—since the Southbridge is

connected to the Northbridge through the FSB, too.

While DMA is certainly beneficial, it means that there is more

competition for the FSB bandwidth. In times with high DMA traffic the

CPU might stall more than usual while waiting for data from the main

memory. There are ways around this given the right hardware. With an

architecture as in Figure 2.3 one can make sure the computation

uses memory on nodes which are not affected by DMA. It is also

possible to attach a Southbridge to each node, equally

distributing the load on the FSB of all the nodes. There are a myriad

of possibilities. In Section 6 we will introduce techniques and

programming interfaces which help achieving the improvements which are

possible in software.

Finally it should be mentioned that some cheap systems have graphics

systems without separate, dedicated video RAM. Those systems use

parts of the main memory as video RAM. Since access to the video RAM

is frequent (for a 1024x768 display with 16 bpp at 60Hz we are talking

94MB/s) and system memory, unlike RAM on graphics cards, does not have

two ports this can substantially influence the systems performance

and especially the latency. It is best to ignore such systems

when performance is a priority. They are more trouble than they are worth.

People buying those machines know they will not get the best

performance.

Memory part 2: CPU caches

[Editor's note: This is the second installment in Ulrich Drepper's "What

every programmer should know about memory" document. Those who have not

read the first part will

likely want to start there. This is good stuff, and we once again thank

Ulrich for allowing us to publish it.

One quick request: in a document of this length there are bound to be a few

typographical errors remaining. If you find one, and wish to see it

corrected, please let us know via mail to lwn@lwn.net rather than by

posting a comment. That way we will be sure to incorporate the fix and get

it back into Ulrich's copy of the document and other readers will not have

to plow through uninteresting comments.]

CPUs are today much more sophisticated than they were only 25 years

ago. In those days, the frequency of the CPU core was at a level

equivalent to that of the memory bus. Memory access was only a bit slower

than register access. But this changed dramatically in the early

90s, when CPU designers increased the frequency of the CPU

core but the frequency of the memory bus and the performance of RAM

chips did not increase proportionally. This is not due to the fact

that faster RAM could not be built, as explained in the previous

section. It is possible but it is not economical. RAM as fast as current

CPU cores is orders of magnitude more expensive than any dynamic

RAM.

If the choice is between a machine with very little, very fast RAM and

a machine with a lot of relatively fast RAM, the second will always

win given a working set size which exceeds the small RAM size and the

cost of accessing secondary storage media such as hard drives. The

problem here is the speed of secondary storage, usually hard disks,

which must be used to hold the swapped out part of the working set.

Accessing those disks is orders of magnitude slower than even DRAM

access.

Fortunately it does not have to be an all-or-nothing decision. A

computer can have a small amount of high-speed SRAM in addition to the

large amount of DRAM. One possible implementation would be to

dedicate a certain area of the address space of the processor as

containing the SRAM and the rest the DRAM. The task of the operating

system would then be to optimally distribute data to make use of the

SRAM. Basically, the SRAM serves in this situation as an extension of

the register set of the processor.

While this is a possible implementation it is not viable. Ignoring

the problem of mapping the physical resources of such SRAM-backed

memory to the virtual address spaces of the processes (which by itself

is terribly hard) this approach would require each process to

administer in software the allocation of this memory region. The size

of the memory region can vary from processor to processor (i.e.,

processors have different amounts of the expensive SRAM-backed memory).

Each module which makes up part of a program will claim its share of the

fast memory, which introduces additional costs through synchronization

requirements. In short, the gains of having fast memory would be

eaten up completely by the overhead of administering the resources.

So, instead of putting the SRAM under the control of the OS or user, it

becomes a resource which is transparently used and administered by

the processors. In this mode, SRAM is used to make temporary copies of (to

cache, in other words) data in main memory which is likely to be used soon

by the processor. This is possible because program code and data has

temporal and spatial locality. This means that, over short periods of time,

there is a good chance that the same code or data gets reused. For

code this means that there are most likely loops in the code so that

the same code gets executed over and over again (the perfect case for

spatial locality). Data accesses are also ideally limited to

small regions. Even if the memory used over short time periods is not

close together there is a high chance that the same data will be reused before long

(temporal locality). For code this means, for instance, that

in a loop a function call is made and that function is located

elsewhere in the address space. The function may be distant in memory, but

calls to that function will be close in time. For data it means that the total

amount of memory used at one time (the working set size) is ideally

limited but the memory used, as a result of the random access

nature of RAM, is not close together. Realizing that locality

exists is key to the concept of CPU caches as we use them today.

A simple computation can show how effective caches can theoretically

be. Assume access to main memory takes 200 cycles and access to the

cache memory take 15 cycles. Then code using 100 data elements 100

times each will spend 2,000,000 cycles on memory operations if there is no

cache and only 168,500 cycles if all data can be cached. That is an

improvement of 91.5%.

The size of the SRAM used for caches is many times smaller than the

main memory. In the author's experience with workstations with CPU caches the

cache size has always been around 1/1000th of the size of the main memory

(today: 4MB cache and 4GB main memory). This alone does not

constitute a problem. If the size of the working set (the set of data

currently worked on) is smaller than the cache size it does not

matter. But computers do not have large main memories for no reason.

The working set is bound to be larger than the cache. This is especially true for

systems running multiple processes where the size of the working set is the sum of

the sizes of all the individual processes and the kernel.

What is needed to deal with the limited size of the cache is a set of good

strategies to determine what should be cached at any given time.

Since not all data of the working set is used at

exactly the same time we can use techniques to temporarily

replace some data in the cache with other data. And maybe this can be

done before the data is actually needed. This prefetching would

remove some of the costs of accessing main memory since it happens

asynchronously with respect to the execution of the program. All these techniques and

more can be used to make the cache appear bigger than it actually is.

We will discuss them in Section 3.3. Once all these

techniques are exploited it is up to the programmer to help the

processor. How this can be done will be discussed in Section 6.

3.1 CPU Caches in the Big Picture

Before diving into technical details of the implementation of CPU

caches some readers might find it useful to first see in some more

details how caches fit into the “big picture” of a modern computer

system.

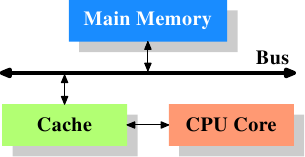

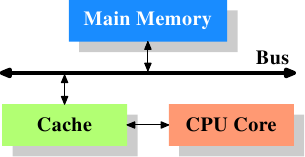

Figure 3.1: Minimum Cache Configuration

Figure 3.1 shows the minimum cache configuration. It

corresponds to the architecture which could be found in early systems

which deployed CPU caches. The CPU core is no longer directly

connected to the main memory. {In even earlier systems the

cache was attached to the system bus just like the CPU and the main

memory. This was more a hack than a real solution.} All loads and

stores have to go through the cache. The connection between the CPU

core and the cache is a special, fast connection. In a simplified

representation, the main memory and the cache are connected to the

system bus which can also be used for communication with other

components of the system. We introduced the system bus as “FSB” which

is the name in use today; see Section 2.2. In this section we

ignore the Northbridge; it is assumed to be present to facilitate the

communication of the CPU(s) with the main memory.

Even though computers for the last several decades have used the von Neumann

architecture, experience has shown that it is of advantage to separate the

caches used for code and for data. Intel has used separate code and data

caches since 1993 and never looked back. The memory regions needed

for code and data are pretty much independent of each other, which is why independent

caches work better. In recent years another advantage emerged:

the instruction decoding step for the most common processors is

slow; caching decoded instructions can speed up the execution,

especially when the pipeline is empty due to incorrectly predicted or

impossible-to-predict branches.

Soon after the introduction of the cache the system got more

complicated. The speed difference between the cache and the main

memory increased again, to a point that another level of cache was

added, bigger and slower than the first-level cache. Only increasing

the size of the first-level cache was not an option for economical reasons.

Today, there are even machines with three levels of cache in regular

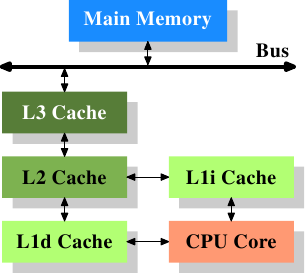

use. A system with such a processor looks like

Figure 3.2. With the increase on the number of cores in a

single CPU the number of cache levels might increase in future even

more.

Figure 3.2: Processor with Level 3 Cache

Figure 3.2 shows three levels of cache and introduces the

nomenclature we will use in the remainder of the document. L1d is the

level 1 data cache, L1i the level 1 instruction cache, etc. Note that

this is a schematic; the data flow in reality need not pass through

any of the higher-level caches on the way from the core to the main

memory. CPU designers have a lot of freedom designing the interfaces

of the caches. For programmers these design choices are invisible.

In addition we have processors which have multiple cores and each core

can have multiple “threads”. The difference between a core and a

thread is that separate cores have separate copies of

(almost {Early multi-core processors even had separate

2nd level caches and no 3rd level cache.})

all the hardware resources. The cores can run completely

independently unless they are using the same resources—e.g., the

connections to the outside—at the same time. Threads, on the other

hand, share almost all of the processor's resources. Intel's implementation of

threads has only separate registers for the threads and even that is

limited, some registers are shared. The complete picture for a modern

CPU therefore looks like Figure 3.3.

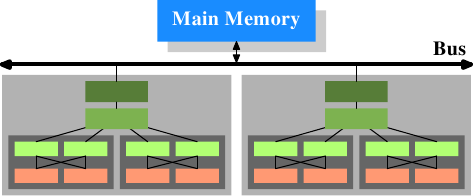

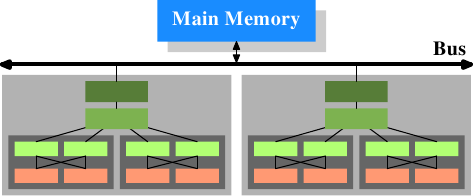

Figure 3.3: Multi processor, multi-core, multi-thread

In this figure we have two processors, each with two cores, each of

which has two threads. The threads share the Level 1 caches. The

cores (shaded in the darker gray) have individual Level 1 caches. All

cores of the CPU share the higher-level caches. The two processors

(the two big boxes shaded in the lighter gray) of course do not share

any caches. All this will be important, especially when we are

discussing the cache effects on multi-process and multi-thread

applications.

3.2 Cache Operation at High Level

To understand the costs and savings of using a cache we have to

combine the knowledge about the machine architecture and RAM

technology from Section 2 with the structure of caches

described in the previous section.

By default all data read or written by the CPU cores is stored in

the cache. There are memory regions which cannot be cached but this

is something only the OS implementers have to be concerned about; it is not

visible to the application programmer. There are also instructions

which allow the programmer to deliberately bypass certain caches. This will be

discussed in Section 6.

If the CPU needs a data word the caches are searched first.

Obviously, the cache cannot contain the content of the entire

main memory (otherwise we would need no cache), but since all memory

addresses are cacheable, each cache entry is tagged using the

address of the data word in the main memory. This way a request to

read or write to an address can search the caches for a matching tag.

The address in this context can be either the virtual or physical

address, varying based on the cache implementation.

Since the tag requires space in addition to the actual memory, it is

inefficient to chose a word as the granularity of the cache. For a

32-bit word on an x86 machine the tag itself might need 32 bits or

more. Furthermore, since spatial locality is one of the principles on

which caches are based, it would be bad to not take this into account.

Since neighboring memory is likely to be used together it should also be

loaded into the cache together. Remember also what we

learned in Section 2.2.1: RAM modules are much more effective

if they can transport many data words in a row without a new CAS or

even RAS signal. So the entries stored in the caches are

not single words but, instead, “lines” of several contiguous words.

In early caches these lines were

32 bytes long; now the norm is 64 bytes. If the memory bus is

64 bits wide this means 8 transfers per cache line. DDR supports this

transport mode efficiently.

When memory content is needed by the processor the entire cache line

is loaded into the L1d. The memory address for each cache line is

computed by masking the address value according to the cache line

size. For a 64 byte cache line this means the low 6 bits are zeroed.

The discarded bits are used as the offset into the cache line. The remaining

bits are in some cases used to locate the line in the cache and as the tag.

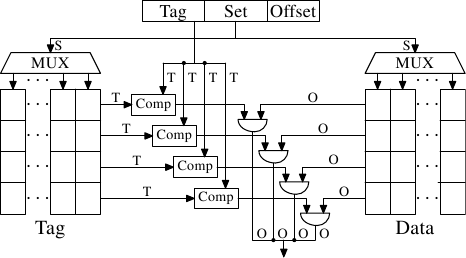

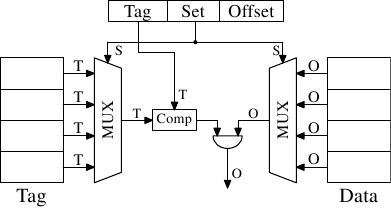

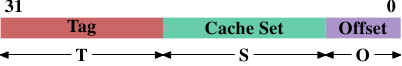

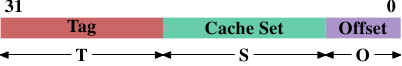

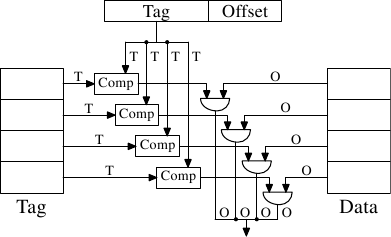

In practice an address value is split into three parts. For a 32-bit

address it might look as follows:

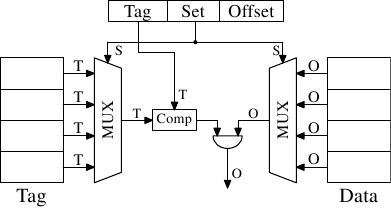

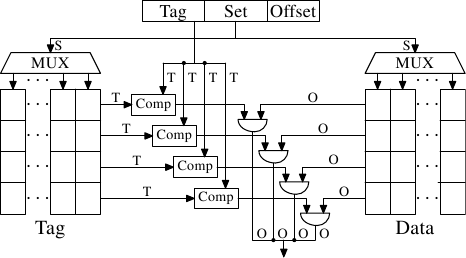

With a cache line size of 2O

the low O bits are

used as the offset into the cache line. The next S bits

select the “cache set”. We will go into more detail soon on why

sets, and not single slots, are used for cache lines. For now it is

sufficient to understand there are 2S sets of cache lines.

This leaves the top 32 - S - O = T bits

which form the tag. These T bits are the value associated

with each cache line to distinguish all the

aliases {All cache lines with the same S part

of the address are known by the same alias.} which are

cached in the same cache set. The S bits used to address the

cache set do not have to be stored since they are the same for all

cache lines in the same set.

When an instruction modifies memory the processor still has to load a

cache line first because no instruction modifies an entire cache line

at once (exception to the rule: write-combining as explained in

Section 6.1). The content of the cache line before the write

operation therefore has to be loaded. It is not possible for a cache

to hold partial cache lines. A cache line which has been written to

and which has not been written back to main memory is said to be

“dirty”. Once it is written the dirty flag is cleared.

To be able to load new data in a cache it is almost always first

necessary to make room in the cache. An eviction from L1d pushes the

cache line down into L2 (which uses the same cache line size). This

of course means room has to be made in L2. This in turn might push the

content into L3 and ultimately into main memory. Each eviction is

progressively more expensive. What is described here is the model for an

exclusive cache as is preferred by modern AMD and VIA

processors. Intel implements inclusive caches {This

generalization is not completely correct. A few caches are exclusive

and some inclusive caches have exclusive cache properties.}

where each cache line

in L1d is also present in L2. Therefore evicting from L1d is much

faster. With enough L2 cache the disadvantage of wasting memory for

content held in two places is minimal and it pays off when evicting. A

possible advantage of an exclusive cache is that loading a new cache line

only has to touch the L1d and not the L2, which could be faster.

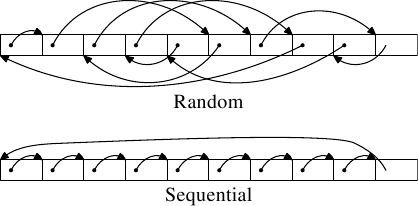

The CPUs are allowed to manage the caches as they like as long as the

memory model defined for the processor architecture is not changed.

It is, for instance, perfectly fine for a processor to take advantage of

little or no memory bus activity and proactively write dirty cache

lines back to main memory. The wide variety of cache architectures

among the processors for the x86 and x86-64, between manufacturers and

even within the models of the same manufacturer, are testament to the

power of the memory model abstraction.

In symmetric multi-processor (SMP) systems the caches of the CPUs

cannot work independently from each other. All processors are

supposed to see the same memory content at all times. The maintenance of

this uniform view of memory is called

“cache coherency”. If a processor were to look simply at its own caches

and main memory it would not see the content of dirty cache lines

in other processors. Providing direct access to the caches of one

processor from another processor would be terribly expensive and a

huge bottleneck. Instead, processors detect when another

processor wants to read or write to a certain cache line.

If a write access is detected and the processor has a clean copy of

the cache line in its cache, this cache line is marked invalid.

Future references will require the cache line to be reloaded. Note

that a read access on another CPU does not necessitate an

invalidation, multiple clean copies can very well be kept around.

More sophisticated cache implementations allow another possibility to

happen. If the cache line which another processor wants to read

from or write to is currently marked dirty in the first processor's cache

a different course of action is needed. In this case the main memory

is out-of-date and the requesting processor must, instead, get the cache line

content from the first processor. Through snooping, the first

processor notices this situation and automatically sends the

requesting processor the data. This action bypasses main memory, though

in some implementations the memory controller is supposed to notice

this direct transfer and store the updated cache line content in main

memory. If the access is for writing the first processor then

invalidates its copy of the local cache line.

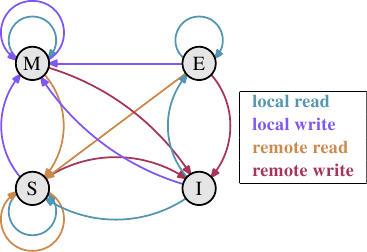

Over time a number of cache coherency protocols have been developed. The

most important is MESI, which we will introduce in Section 3.3.4.

The outcome of all this can be summarized in a few simple

rules:

- A dirty cache line is not present in any other

processor's cache.

- Clean copies of the same cache line can reside in arbitrarily

many caches.

If these rules can be maintained, processors can use their

caches efficiently even in multi-processor systems. All the processors need to do

is to monitor each others' write accesses and compare the addresses

with those in their local caches. In the next section we will go

into a few more details about the implementation and especially the

costs.

Finally, we should at least give an impression of the costs associated

with cache hits and misses. These are the numbers Intel lists

for a Pentium M:

| To Where | Cycles |

|---|

| Register | <= 1 |

| L1d | ~3 |

| L2 | ~14 |

| Main Memory | ~240 |

These are the actual access times measured in CPU cycles. It is

interesting to note that for the on-die L2 cache a large part

(probably even the majority) of the access time is caused by wire delays.

This is a physical limitation which can only get worse with increasing

cache sizes. Only process shrinking (for instance, going from 60nm

for Merom to 45nm for Penryn in Intel's lineup) can improve those numbers.

The numbers in the table look high but, fortunately, the

entire cost does not have to be paid for each occurrence of the cache load and

miss. Some parts of the cost can be hidden. Today's processors all

use internal pipelines of different lengths where the instructions are

decoded and prepared for execution. Part of the preparation is

loading values from memory (or cache) if they are transferred to a

register. If the memory load operation can be started early enough in

the pipeline, it may happen in parallel with other operations and the

entire cost of the load might be hidden. This is

often possible for L1d; for some processors with long pipelines

for L2 as well.

There are many obstacles to starting the memory read early. It might be

as simple as not having sufficient resources for the memory access or

it might be that the final address of the load becomes available

late as the result of another instruction. In these cases the load

costs cannot be hidden (completely).

For write operations the CPU does not necessarily have to wait until

the value is safely stored in memory. As long as the execution of

the following instructions appears to have the same effect as if the

value were stored in memory there is nothing which prevents the CPU from

taking shortcuts. It can start executing the next instruction early.

With the help of shadow registers which can hold values no longer

available in a regular register it is even possible to change

the value which is to be stored in the incomplete write operation.

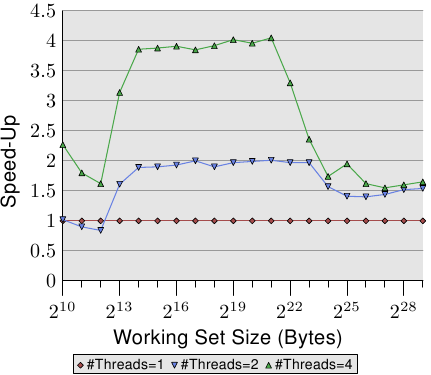

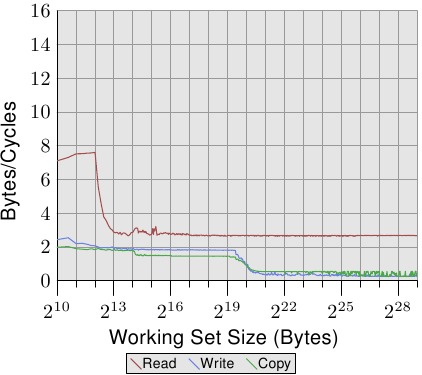

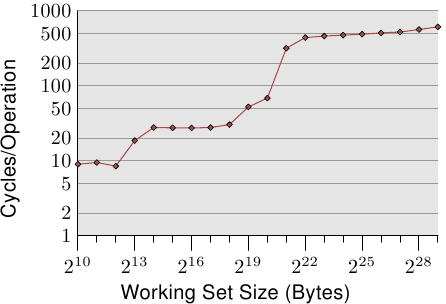

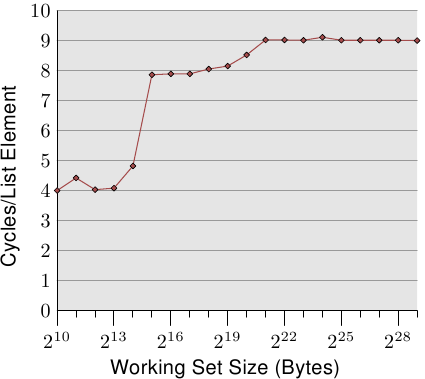

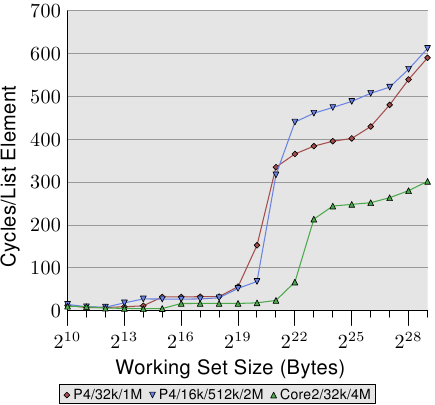

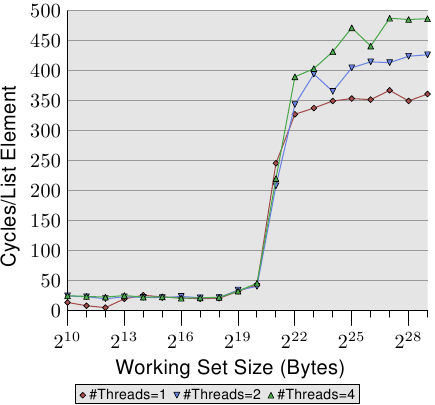

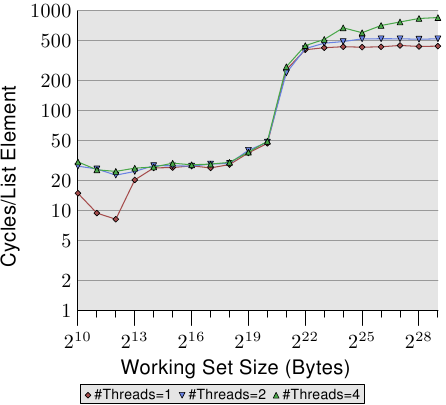

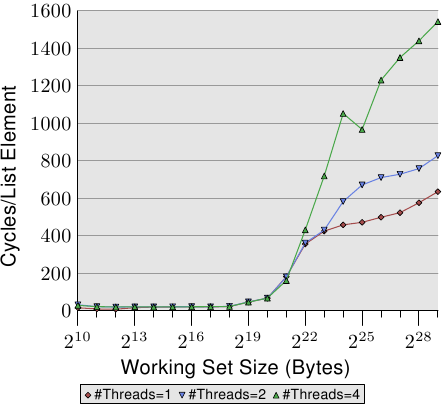

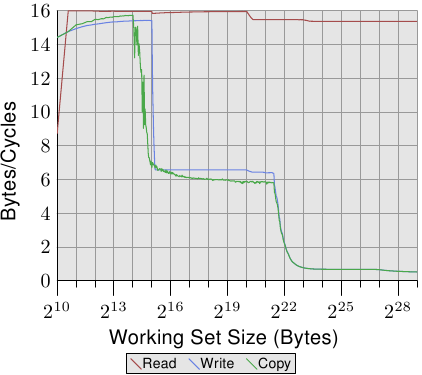

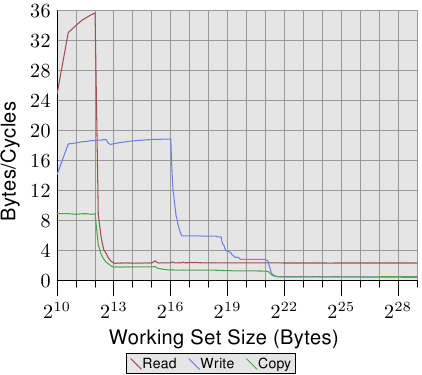

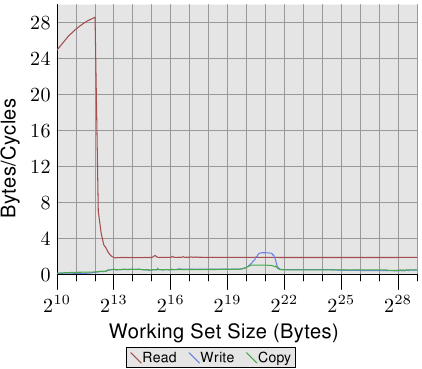

Figure 3.4: Access Times for Random Writes

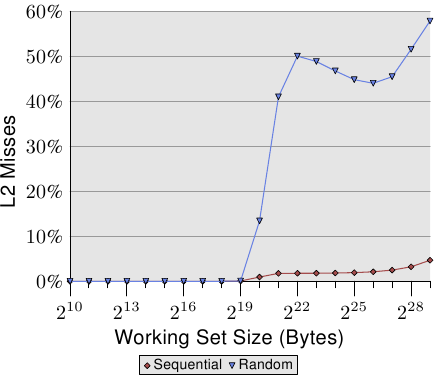

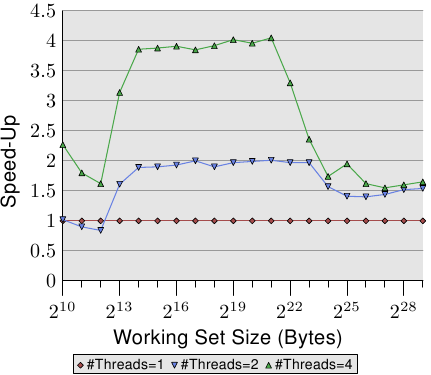

For an illustration of the effects of cache behavior see Figure 3.4. We will talk about

the program which generated the data later; it is a simple simulation of

a program which accesses a configurable amount of memory repeatedly in

a random fashion. Each data item has a fixed size. The number of

elements depends on the selected working set size. The Y–axis shows

the average number of CPU cycles it takes to process one element;

note that the scale for the Y–axis is logarithmic. The same applies

in all the diagrams of this kind to the X–axis. The size of the

working set is always shown in powers of two.

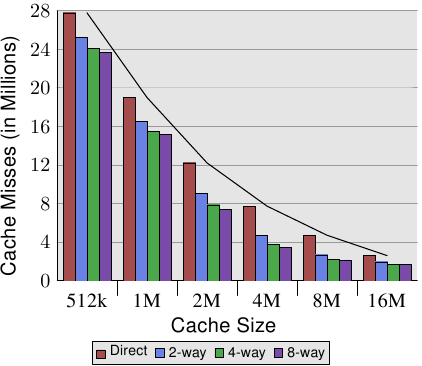

The graph shows three distinct plateaus. This is not surprising: the

specific processor has L1d and L2 caches, but no L3. With some experience we can

deduce that the L1d is 213 bytes in size and that the L2 is

220 bytes in size. If the entire working set fits into the L1d

the cycles per operation on each element is below 10. Once the L1d

size is exceeded the processor has to load data from L2 and the average time

springs up to around 28. Once the L2 is not sufficient anymore the

times jump to 480 cycles and more. This is when many or most operations

have to load data from main memory. And worse: since data is

being modified dirty cache lines have to be written back, too.

This graph should give sufficient motivation to look into coding

improvements which help improve cache usage. We are not talking

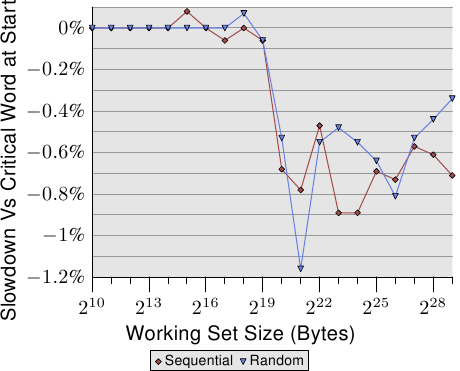

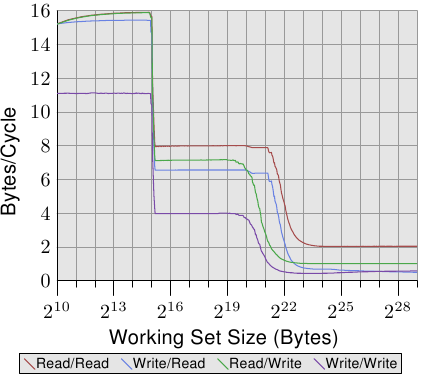

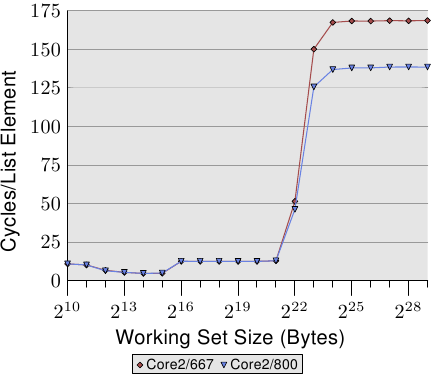

about a few measly percent here; we are talking about orders-of-magnitude